The 6 Traps of Community Engagement (and their remedies)

Kicking off our ongoing series on how to collaborate with users to create thriving places which reflect their needs and desires.

A New Series on Engagement and Accountability

This is the first in a new ongoing series exploring how places and projects can - and should - be more responsive to those most impacted. Over the coming months we’ll explore:

Dynamics around the gathering of input;

The translation of that input into implementation; and

Factors that lead to shared success, or failure.

A Brief History of Community Engagement

Community engagement is now an almost required feature of any public realm project. But what does “community engagement” really mean? How much of it is worthwhile? Can it actually be counter-productive?

Community engagement - the incorporation of input about what is being done from those most impacted by a potential project - arose as a well-intentioned remedy to the effects of insulated mid-century planners who often made sweeping and destructive changes to huge expanses of neighborhoods.

But is the remedy useful? Is it the right medicine? We agree with Charles Marohn of Strong Towns when he wrote Most Public Engagement is Worthless.

So what are the features that make an engagement effort useful and truly shape a project to best serve the people who are most impacted by it?

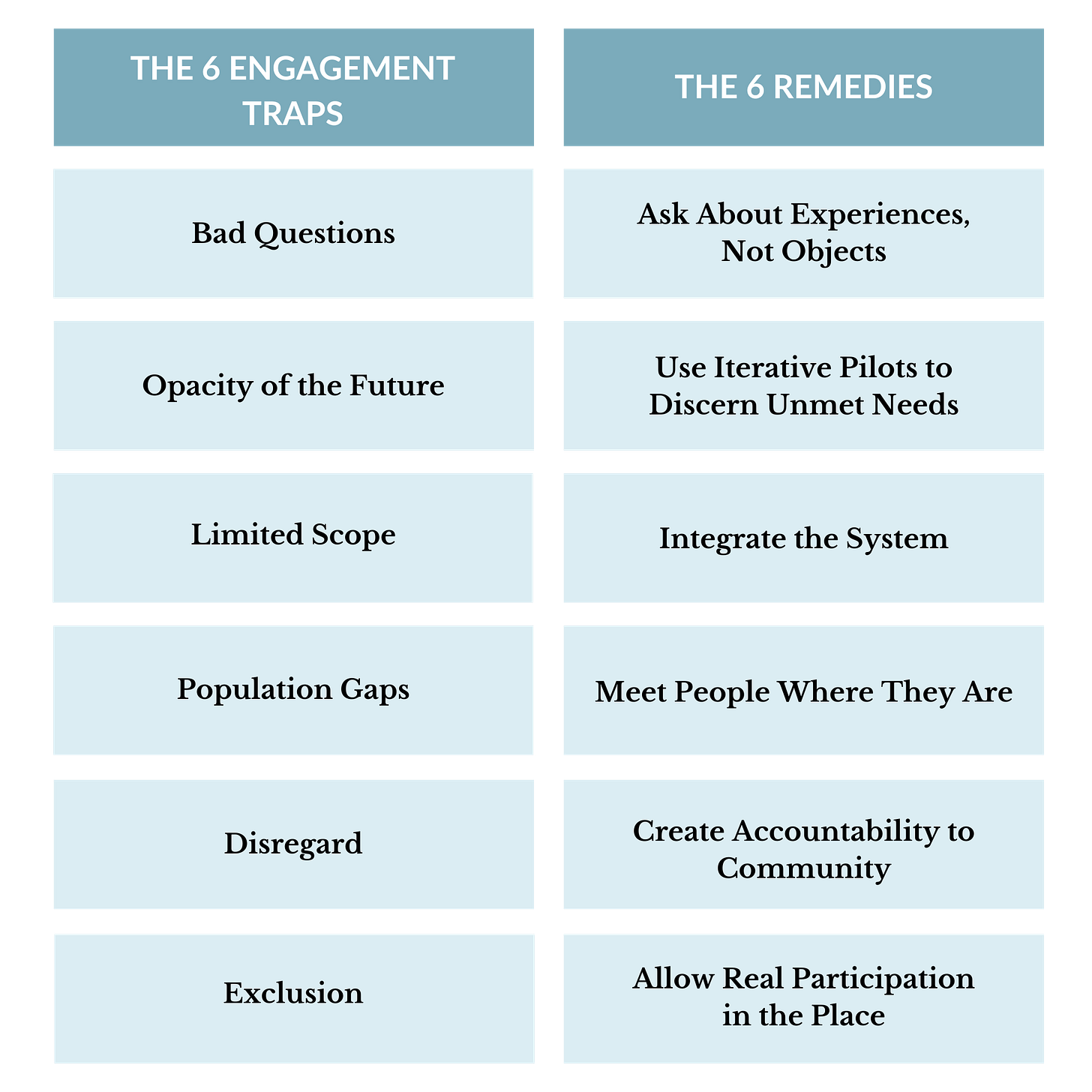

The 6 Engagement Traps

Building off of Marohn's post, why is so much engagement pointless, ineffective, or even disingenuous?

Bad Questions: The questions asked generate responses which actually conceal the true desires and experiences of the responder;

Opacity of the future: Any response to an engagement question has limited value because people can’t really know what they want in the future without seeing it first;

Limited scope: Input is sought only during the design of capital projects with a focus only on the physical environment and little (if any) attention or intention towards translating stated desires or commitments in the life of a place after the ribbon cutting;

Population gaps: The input gathered is from people who don’t fully reflect those most impacted;

Disregard: Those with authority over a project don’t actually care about engagement results;

Exclusion: People are actively punished and prevented from directly shaping their shared spaces themselves, which necessitates exclusively working through a whole host of agents to make improvements

The 6 Remedies

To counter each trap, we’ve deployed the following strategies:

Ask about experiences, not objects: to generating useful answers (“do” vs “see”);

Use iterative pilots to discern unmet needs: allowing you and others to observe how people actually behave before making a big change;

Integrate the system: by going beyond just the design, to incorporate operations, governance, and partnerships as tools to respond to engagement feedback;

Meet people where they are: by making any engagement activity beneficial and convenient on the terms of those who give their time and input;

Create accountability to community: by having incentives that orient those with authority to achieve a community’s goals past the ribbon cutting moment. Which likely requires lengthening the timeline for resource allocation to allow the space to adapt past the typical project completion date;

Allow real participation in the place: by creating rules and guidelines that allow for those who care about the place to do small good things with little to no formal approval needed at any time.